Madurai, is a city known as the heart of Tamil Nadu culture, and not without good reason. It’s a city filled with South Indian architecture, dance, sculptural art, and a storied history tied to legend. Known for its grand Meenakshi Temple, the famed Thirumalai Nayak Mahal, and as the capital of the Pandya Kingdom and central city of Sangam Literature, it’s a storied city of heritage. In my opinion, it’s a city of romance, and Thirumalai Nayak meant this as such. He built, and developed this city with a commitment to artistic and romantic beauty. He made the Madurai Meenakshi Temple as large as it is today, as well as added gopurams and expanded temples all over Tamil Nadu. He was an important patron of the arts — including early Carnatic traditions — helping them flourish during his reign. Bharatnatyam, architecture, sculptures, and all types of art flourished under Thirumalai Nayak. Madurai is a legacy of this, of the Pandyas, Thirumalai Nayak, and his successors. Thirumalai Nayak, specifically, ushered a golden age of Tamil – South Indian art, and I intend to introduce a plan to further this art style.

In this, I layout a plan to develop the city of Madurai further than it has been currently, to reach it’s potential as a romantic city, and an artist hub.

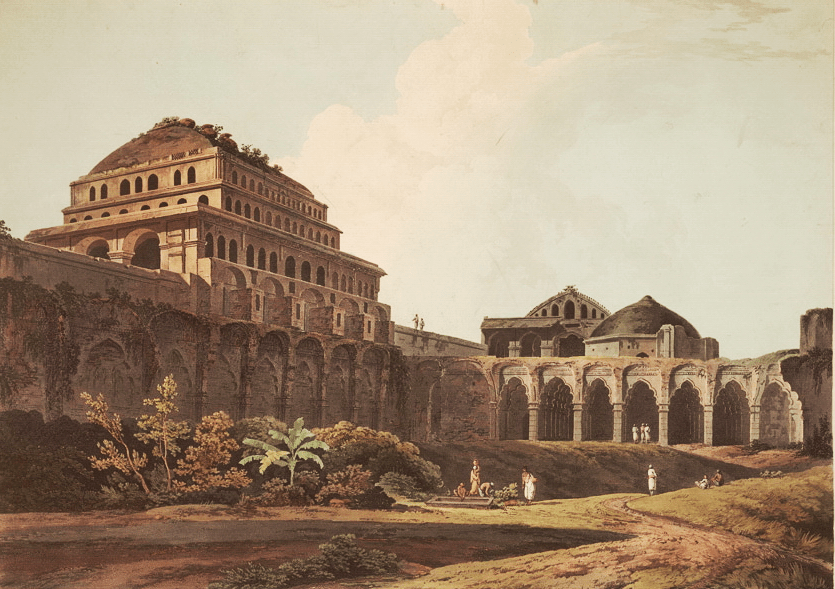

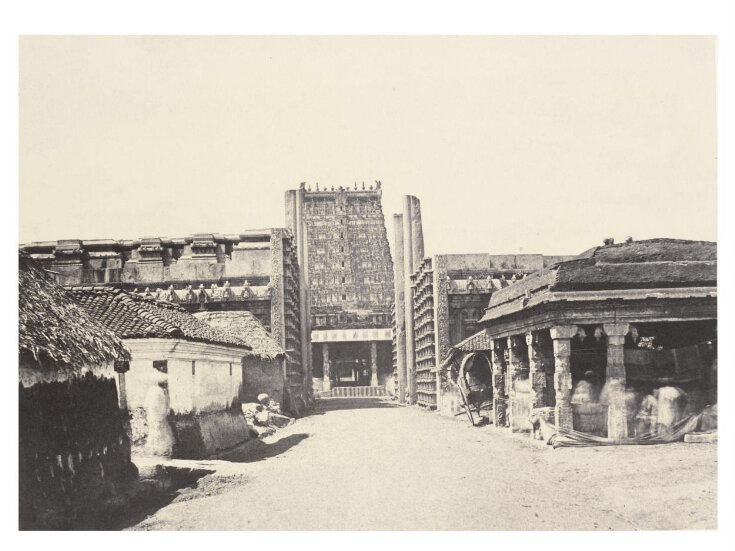

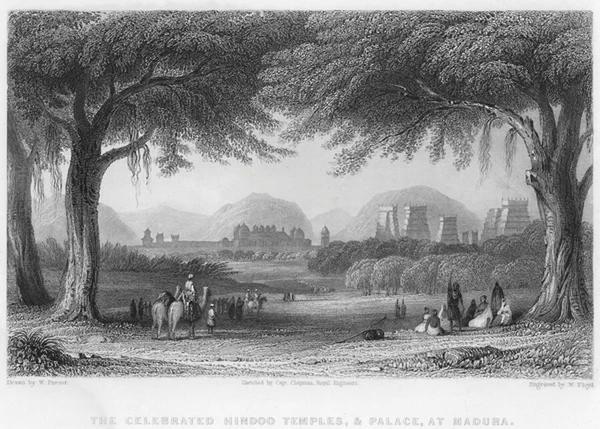

I propose that we expand the rest of the Thirumalai Nayak Mahal, restoring it to its original size, or at least part of it, which was originally about 4 times larger than it was today. Some more remains show, about a century or two later, in 1798 by Thomas Daniel below:

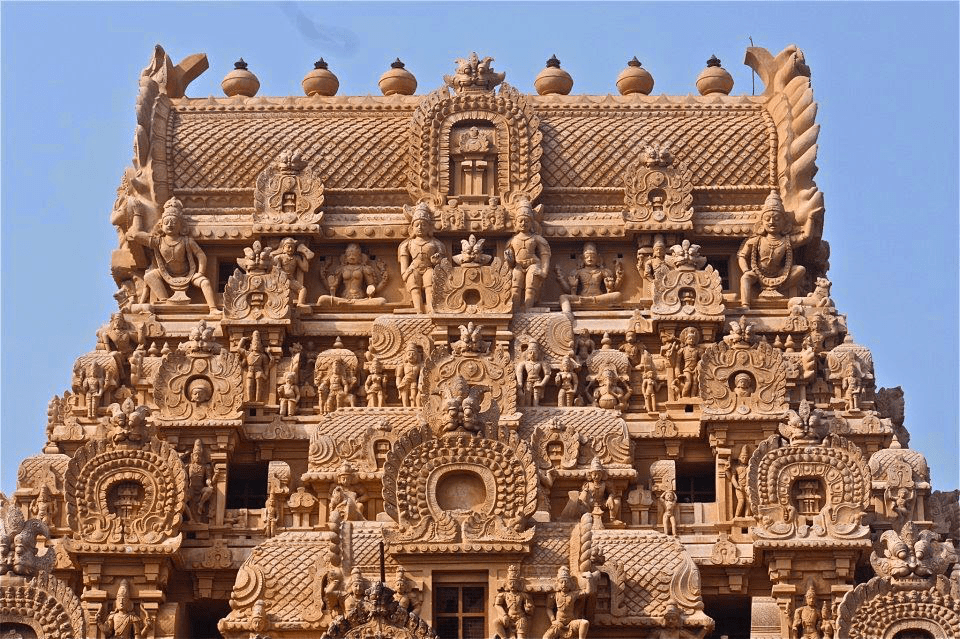

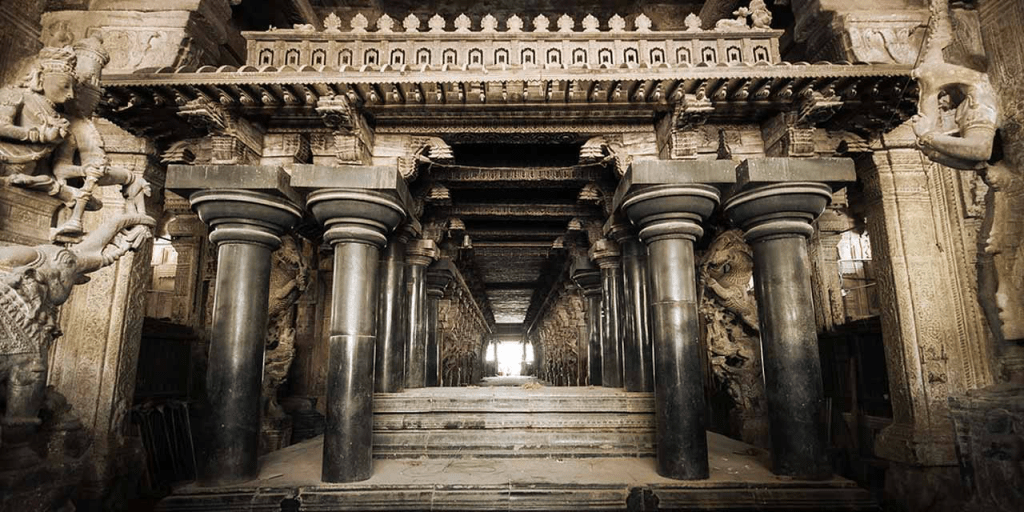

This was prior to further demolition and repurposing for local housing. In the 18th century, the British accounted that the remaining structure was 4 times larger than the structure at the time, though – it’s lost even more since then, as the sections open to the outdoors with the pillared halls are no longer standing today. The current structure is a testament to South Indian art, and it’s potential for Indian architecture, expanding the existing palace structure of India with South Indian elements:

I propose that we rebuild this structure, finding whatever remnants of the scale. Either that, or we expand it.

One large part, that’s evident in Thirumalai Nayak Mahal, but also throughout Tamil Nadu, in my research, is the use of artificial paints – which, may not have the same appeal as natural paint on lime plaster – which is a harmonious combo, shown in palaces in the north, as shown below:

Both Thirumalai Nayak Palace and the Rajasthani palace shown above use lime plaster for the superstructure, everything above the columns- the difference comes in the choice of paints – high quality natural paints vs artificial chemical paints. The choice for which is not clear in Tamil Nadu’s case – though seeing the green example in the top, I’d push for that ideal.

We can use it’s style of architecture leading it among waterways which we should add to the Madurai Landscape:

I propose we apply the Venetian style of canal based cities, to Madurai, or at least allow the rivers to run through the city. We would use the storied Vaigai River, rich with legend:

to initiate this, running it through the city like the Siene of Paris, having tributaries through the city with canals like Venice. See the AI generated image of the proposed idea below:

As you can see, there are boats running through this river, and canals through the city. The architecture along the rivers, show buildings with arches and terracotta roofing (much like Venice, as we share terracotta roofing), which, I propose we either

1. Use a distinct – South Indian temple-architecture inspired palatial arches

2. Use Nayak Era arches – which are a northern and southern blend of palatial architecture

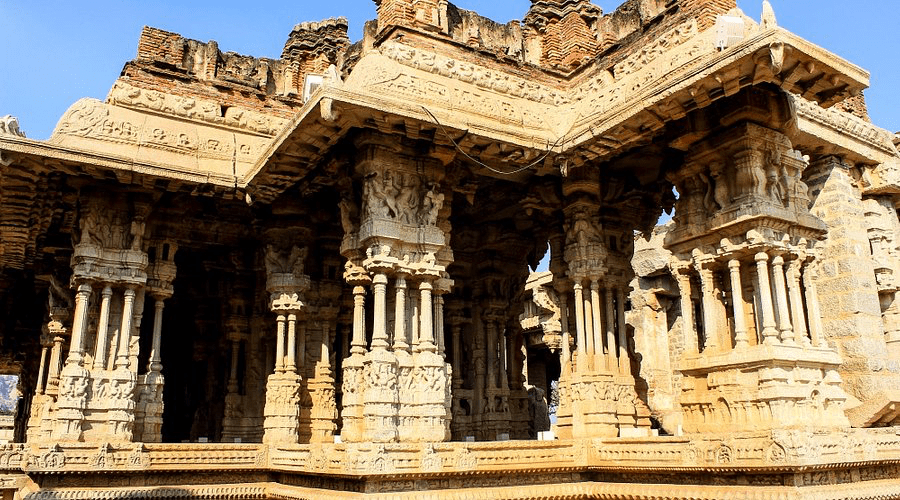

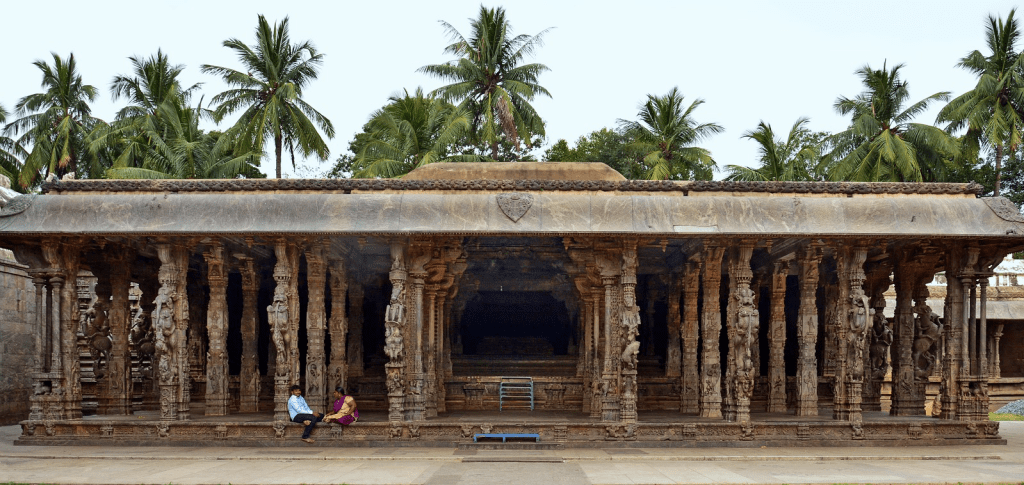

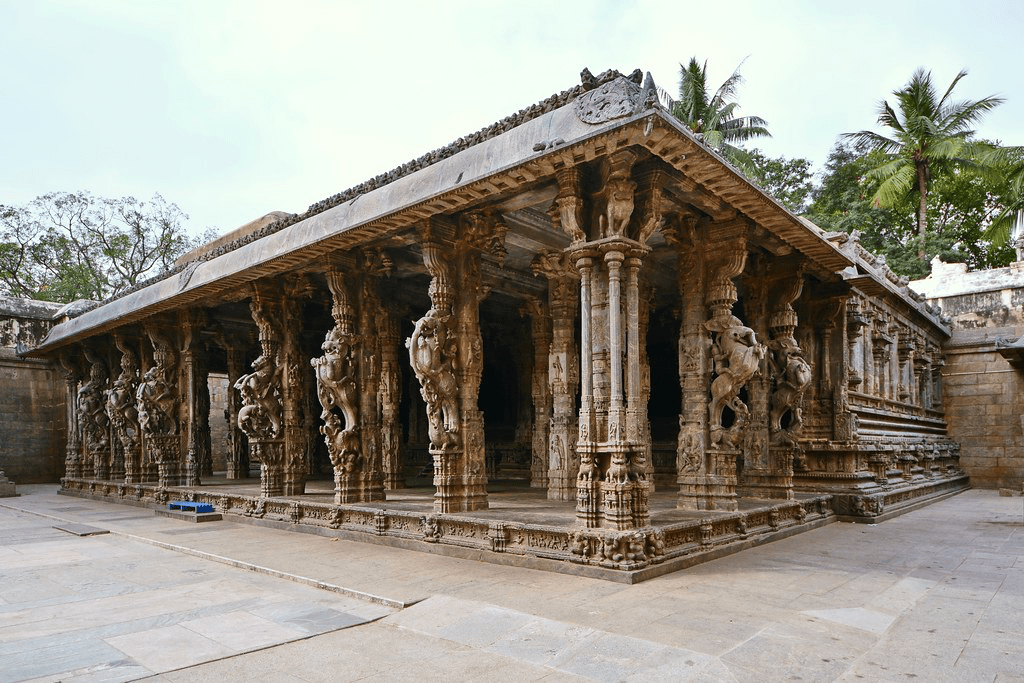

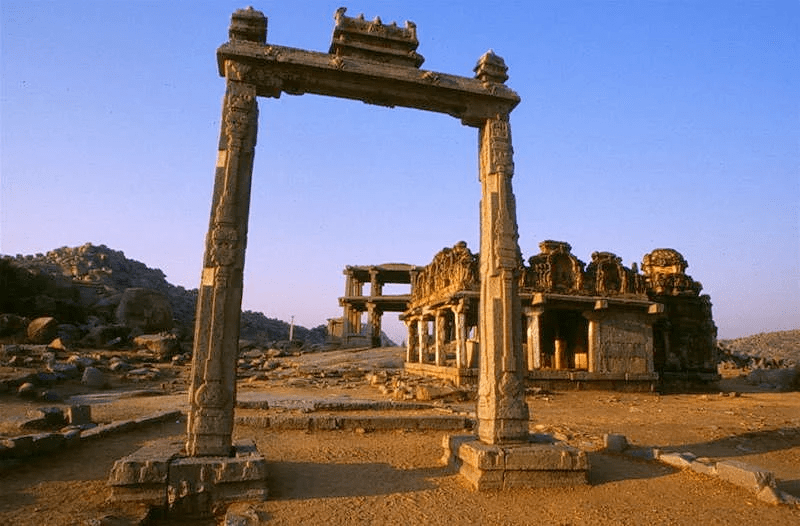

For option 1, we could base the buildings on that of such structures that were built as mandalas in temples as the base for palatial design – such as that of the Vitthala Temple in Hampi, as seen below:

Another example is the Jalakandeswara temple Mandapam

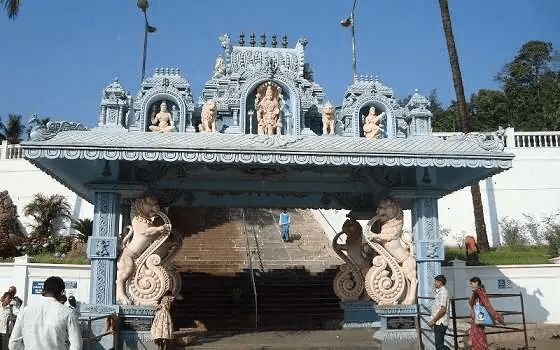

The Sri Ramar Temple of Salem uses this form, with red-black granite instead:

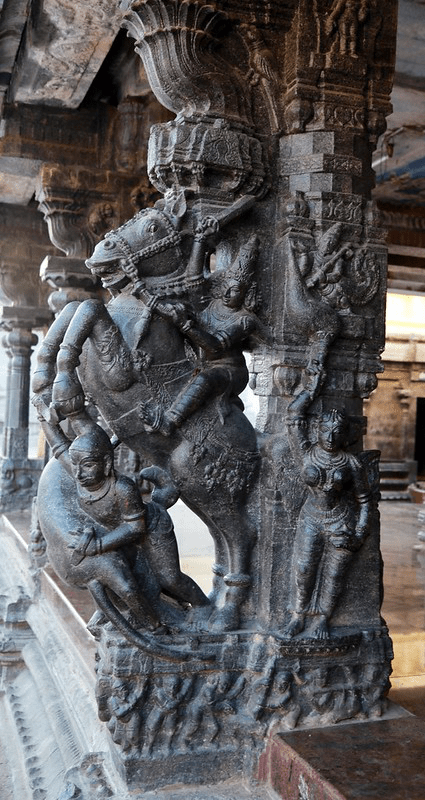

This style allows for the use of multi-layered musical pillars,

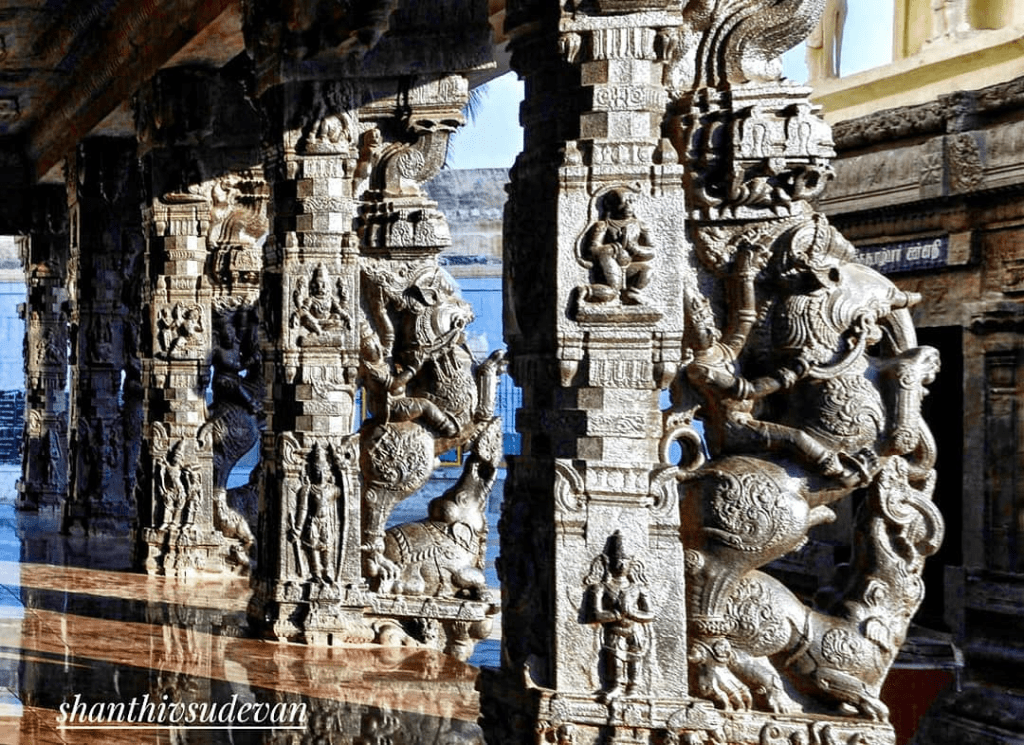

used at Sri Rama Temple in Salem, while used in it’s most developed & grand form in temples such as the Nellaiappar Temple in Tirunelveli, and the Thanumalayan Temple in Suchindram. Sculptures of persona can be added to the layered pillars, as shown below, with floral designs on the base of the pillars:

This form could be used with varied materials – of colors white, green, red, black, which could have a palatial appearance. The ceiling could use South Indian style temple roofings of the following styles:

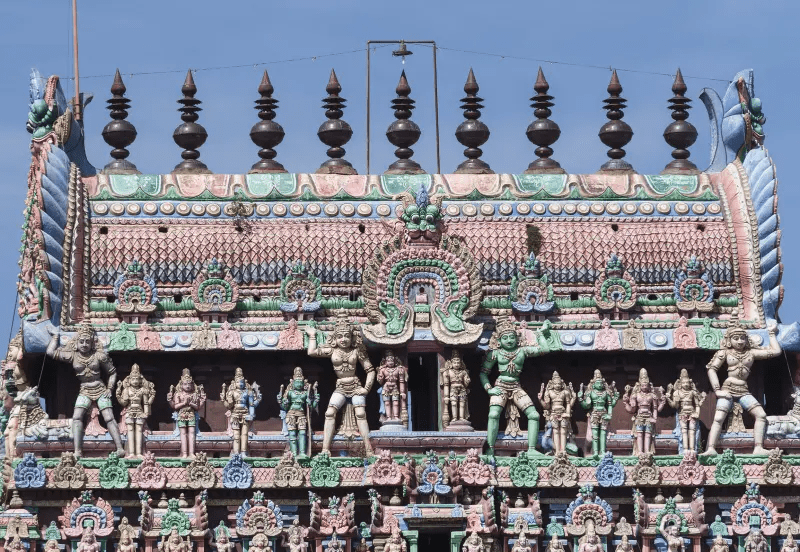

Or Tamil Gopuram tube roofing with fiery Yaazhi edges

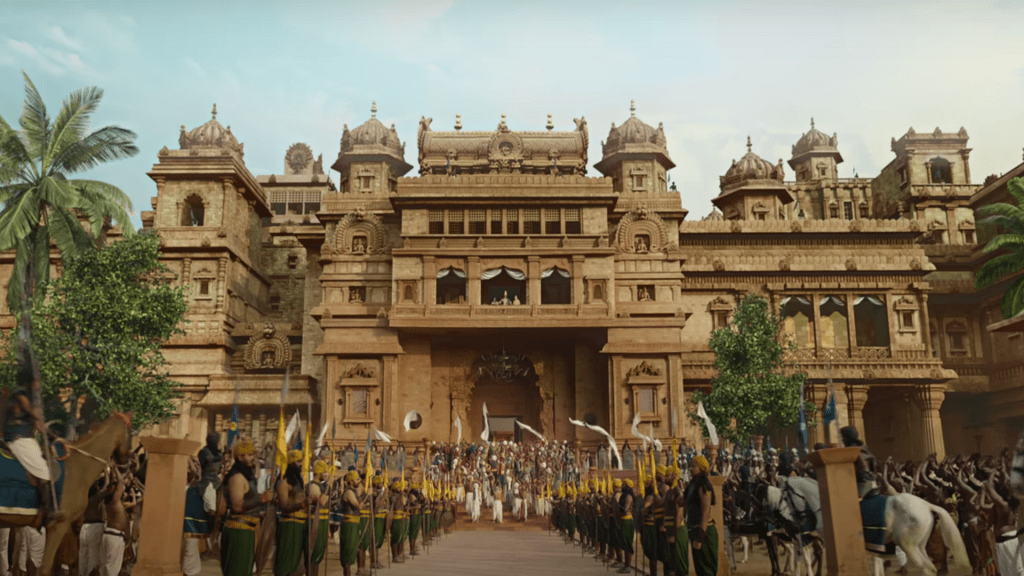

An example of which the referenced South Indian elements in which this is used is below, from the Chola palace in Ponniyin Selvan:

The Ponniyin Selvan palace uses such tubular/angukar domes characteristic of the South Indian style. While it uses Indo-Islamic elements, it retains a South Indian appearance with the use of the referenced domes and Yaazhi + fiery adornments. This is more in line with the vision that was referenced for option 1.

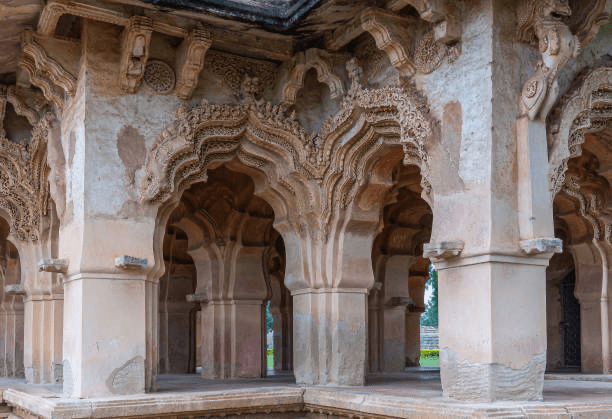

For option 2, we could use Nayak Era arches such as those of the exterior portions of the demolished parts of the Thirumalai Nayak Mahal, as shown in Daniell’s painting, along the river, leading up to the palace. Outside of foundational metal and reinforced concrete, the bridges should be of Charnockite and Granite, with Charnockite as the load bearing structure and granite as the above water superstructure, carved with South Indian designs, such as in the image below from Thirumalai Nayak Mahal

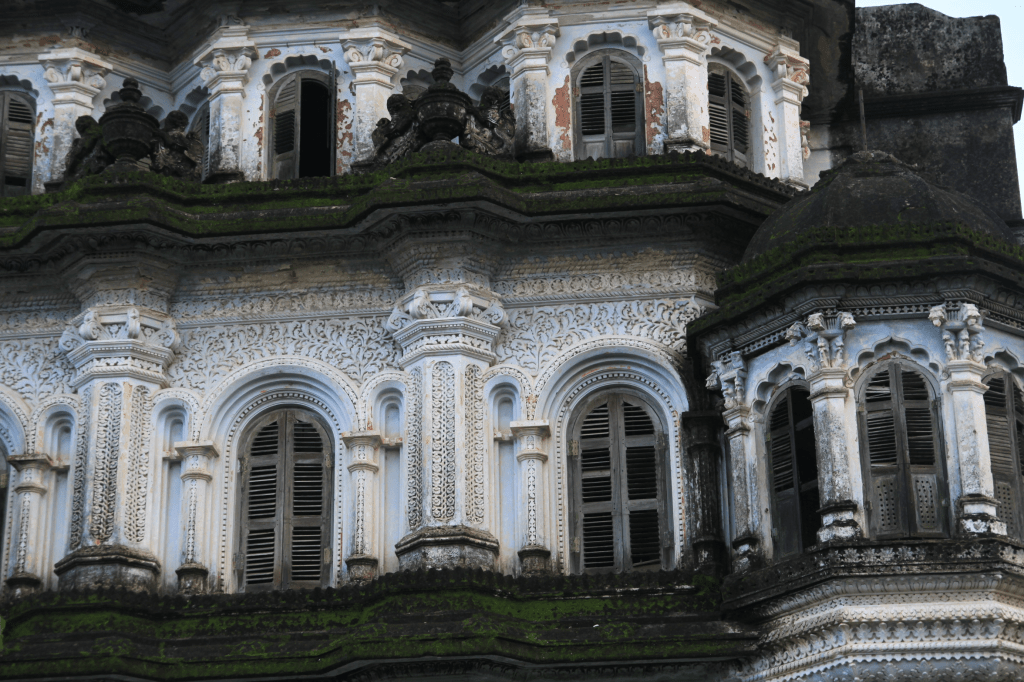

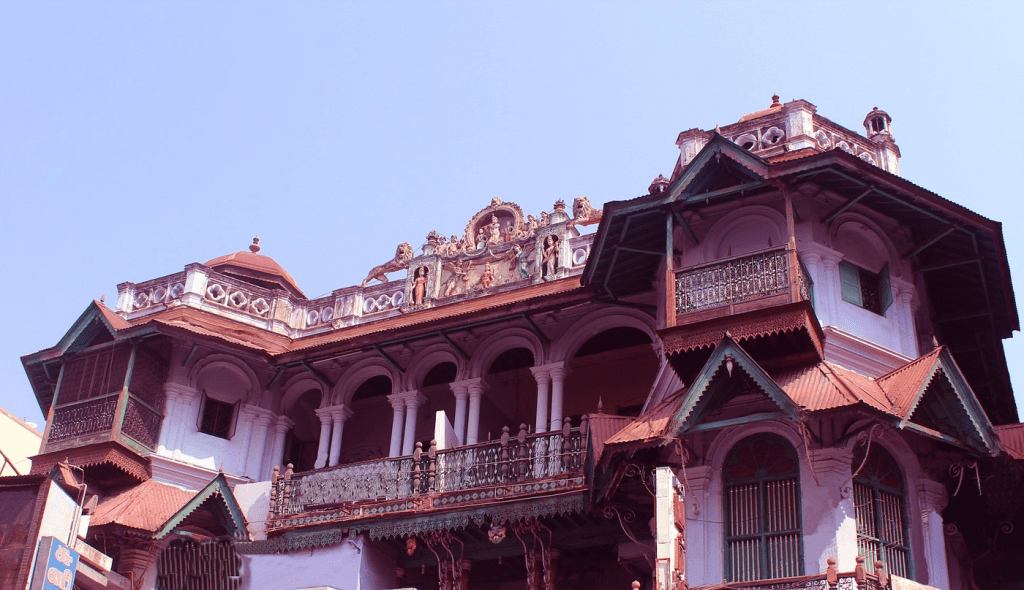

More examples of this style of architecture are as below – in Nayak Era Palaces, to be adapted to the Madurai’s buildings, in monumental park arches, adorned buildings, etc. See the forgotten, ruined Udarpalayam Palace below, which used similar materials to achieve the Nayak style

The Bodinayakkannur Zamin Palace continues with this style, as seen below:

Ettaiyapuram Palace also follows this style, with some more characteristic South Indian domes

However, the windows of Ettaiyapuram Palace do not use distinctly South Indian window styles – which is a deviation of the style – as well as with the adornments around them using some South Indian styles, but largely European styles:

These are all made in the Indo-Saracenic style, which is built off of the Indo-Iranian style. The Thirumalai Nayak Mahal, however, was a frontrunner in this

When comparing these 2 options, we must take into consideration the following:

- According to current sources, the Thirumalai Nayak Mahal was one of the oldest examples of the Indo-Saracenic – Indo-Iranian Palace Architecture used in Hindu settings. It had only a few other examples to date to learn from: the Datia Palace & Man Mandir Palace (Gwalior Fort) in Madhya Pradesh, the Lotus Mahal in Hampi, Karnataka. It preceded many of the famous palaces in India that are highly visited today – including the City Palace & Hawa Mahal in Jaipur, the Jaisalmer Haveli, the lake Palace in Udaipur, etc. It’s a significant architectural contribution. It represents an early and distinct development in Indo-Saracenic and South Indian palace architecture, emerging around the same period as many Rajput innovations, and in some cases even earlier. The use of marble for Indo-Iranian – Indo-Saracenic architecture was founded in the same time period, applied to the Amer Palace in Jaipur most notably, at the earliest during the 16th-17th centuries – built around the same time period as the Thirumalai Nayak Mahal. With that in mind, Thirumalai Nayak Mahal is a huge innovation. The palaces of Tamil Nadu that shared this style noted in the images the reference to Thirumalai Nayak Mahal in option 2, followed this innovative hybrid South Indian – Indo-Saracenic style.

- We can choose to design a distinctly South Indian style alone. Comparing a (larger) gateway in Tirunelveli, Tamil Nadu that’s made in the Indo-Saracenic style to a (smaller) gateway in Hampi, Karnataka made in the South Indian style below:

The design of the scalloped arch gateway in Tirunelveli is in line with pan-Indian styles, with possible origination from Hampi’s Lotus Mahal, Mughal styles, and early Kashmiri Scalloped Arch styles –

used throughout India, while the designs in Hampi, Thirunangur, and Hornadu are distinctly in the South Indian style. It depends on what we want to emphasize. With South Indian gateways, palatial architecture, and otherwise, there’s much to be developed and applied to alternative-purpose buildings, and as such holds a lot of potential. On the other alternative – the scalloped arch style that is referenced is already such an iconic and beautiful style to use.

I’ve designed styles of my own – with South Indian elements – combining Tamil, Kerala, Indo-Saracenic, and Beaux-Arts styles to be used for Madurai – and global pan-cultural settings:

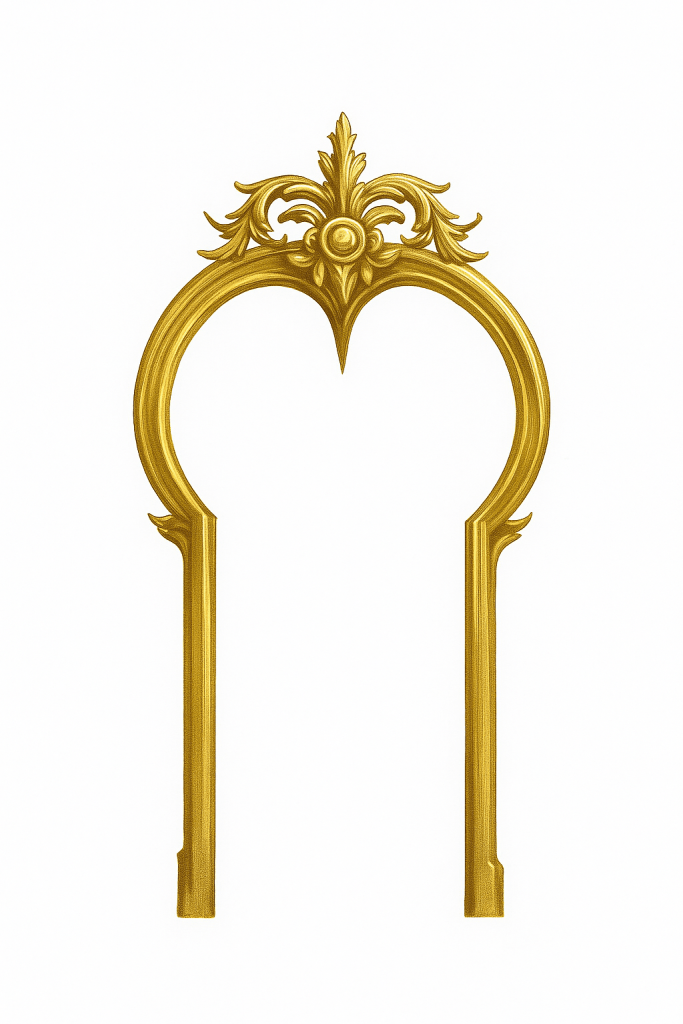

A design series, the “South Indian Horseshoe” – “Ugravalam Arch” ©

It could be used from cities like Madurai – to NYC, where it could fit with Gothic, Beax-Arts, Art Deco, or any other style in the city – and at subway entrances as well. We could use Gilt Bronze, which would fit in the New Yort Luxe Art Deco School, or Brass, in the South Indian School of Architecture.

The scalloped arch, also known as the multifoil arch, that we see all over most of the major palaces in India is a shared design that we see as an innovation in India, Iran, and Islamic Spain. The downward-pointed horseshoe arch with Yaazhi or an animal motif centre, however, is characteristic of South Indian Prabhavali’s, or sacred archways.

The gable in Kerala, while extensively used around the world, has distinct elements, notably the large arrow-like keystone in the middle, with a mix of global adornments and native elements.

I wanted to create an arch that’s Southern Indian in origin – while being a design that would be agnostic – able to be used pan-culturally. I took the long, central arrow-like keystone from the Kerala Gable and transposed it onto the scalloped horseshoe arch.

My results were as such –

above: a horseshoe arch that opens upward with an arrow-like central keystone, and below: a downward prabhavali-like scalloped arch.

These designs are intended to be customizable, and can be adapted to different settings, motifs, etc. It could work in Indian, Beaux Arts, Art Deco, Gothic, Indo-Islamic, and other styles in many different settings, from Madurai to New York City to Berlin.

In addition, we should add adorned buildings, monuments, and arches in the style of Kerala architecture. See the photos of Krishnapuram Palace in Allapuzha below:

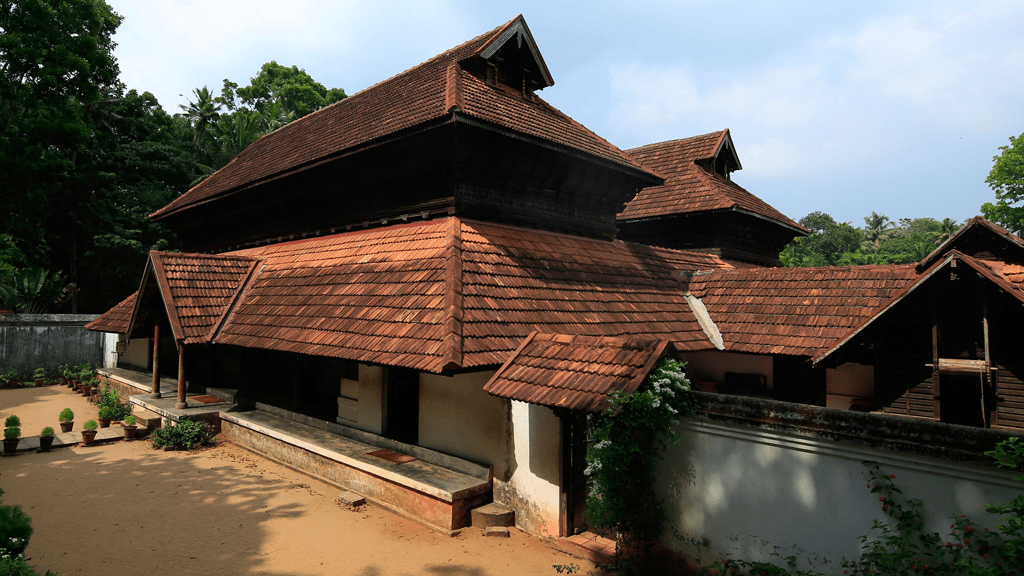

For the river canals, they should extend far enough, so that we can have houses along the river, such as the below setting in Kerala, with expanded Kerala architecture in the city, where possible:

we need to restore the general vernacular housing across the city, from traditional terracotta roofing homes similar to Malayalee styles above, as well as traditional Tamil city homes, such as below from Kolam homes in Madurai

I propose for these houses that we further develop this style, while also furthering such South Indian elements – the Nayak style, for the roofing, lattices, and windows, as well as South Indian pillars.

Outside of the rivers, we already have ponds and such structures in Madurai, like the Vandiyur Mariamman Teppakulam, primarily built for aesthetic appeal. We should aim to add to this type of structures, enhancing the pond central sculptures to use granite carvings, and possibly fountains.

The history of materials in Tamil Nadu, as with any state in India, is based on the local availability and adaption to the weather, which in Madurai’s case, is of monsoons and tropical, humid climate. To adapt as such, they used the following materials

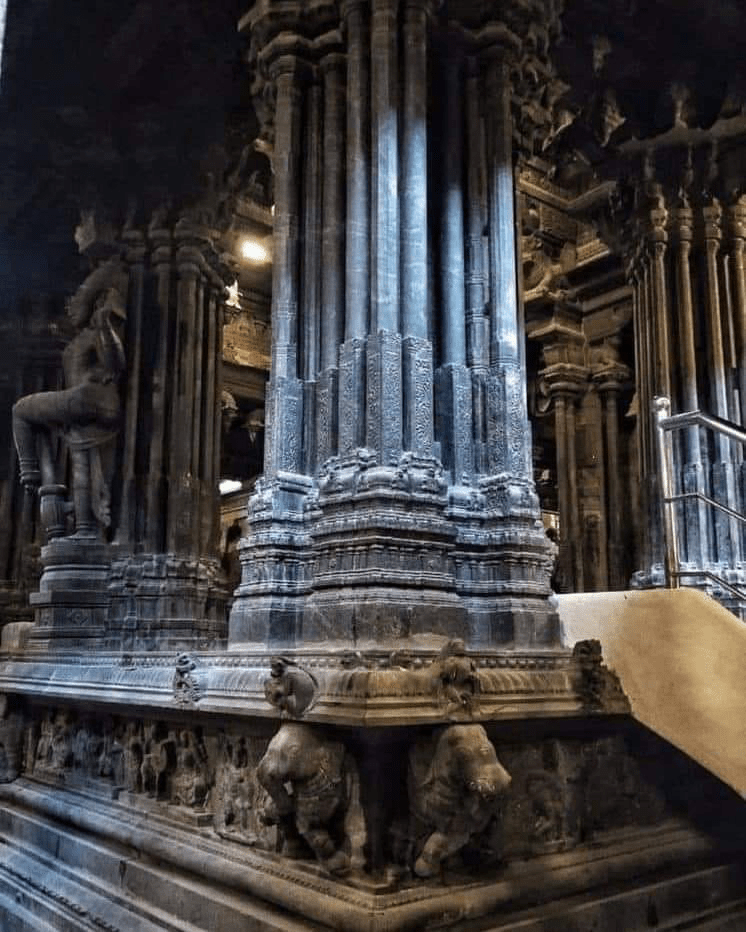

- Granite – as bases of gopurams, the full structure of the Great Living Chola temples aside from the Nayak and Maratha additions, and the interiors of the temples, particularly all throughout Tamil Nadu. Granite is the most abundant building stone of Tamil Nadu, and it’s both highly durable and resistant to mold in monsoon weather, allowing it to last through millenia. Most of Tamil Nadu’s interior architectural heritage in temples and other monumental structures is largely based on granite construction.

- Brick – used as the superstructures of gopurams and vernacular houses, sometimes out of laterite

- Stucco/Lime Plaster (Chunam) – used for ornamented friezes, such as carved gopurams, palatial friezes, luxury home carvings, and general exterior wall plasters for housing.

- Timber – used often for vernacular construction in Tamil Nadu, and all throughout for vernacular, palace, and temple construction in Kerala.

- Soapstone – used in covered spaces, as it’s soft when quarried up unto installation, and may lack the ability to support large structures as a load bearing base, though it works well in the Belur region of Karnataka, where many Hoysala temples are constructed out of the material. It’s available in pockets of Tamil Nadu, though not as much as in Karnataka. Still, it is a eco-realistic material for use in Tamil Nadu.

We could use more granite, along with charnockite, an abundant stone for base durability. Using granite can allow us to create stable, lasting sculptures. For bridges and other structures, to smoothen out the granite blocks we can take inspiration from Portugal’s Porto:

The Portuguese were able to polish and smoothen the granite into stone blocks, commonly used in European construction, though the granite has particularly dark appeal to it. The Spanish El Escorial, a palace for the King of Spain, was almost entirely made of granite as well, with stone granite blocks:

I propose, that we use this for our construction, with the South Indian – Nayak school of design.

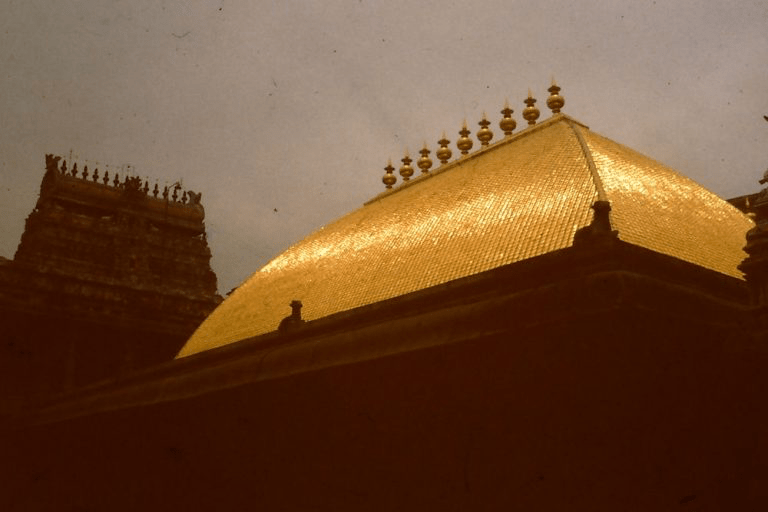

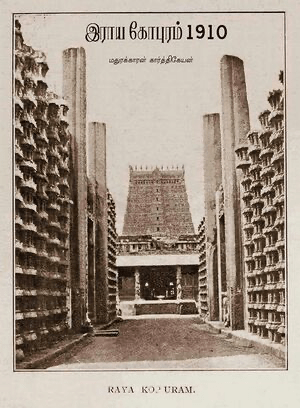

I propose that we complete the Raya Gopuram, outside the Madurai Meenakshi Temple:

This Raya Gopuram is the massive base of an unfinished gopuram, meant to stand around 300 feet tall, which would be the largest gopuram to exist. I propose that we commit to this plan, innovating with more granite to the structure.

Furthermore, we should expand the use of soapstone, for intricate temple sculptures, mandapas, as well as inner palace ornamentation. Here is a use of soapstone in the Madurai Meenakshi temple, for the Nandi Mandapa, with carved granite interiors of the temple as the background:

As shown, it’s more finely carved than many granite sculptures, as it’s softer and is able to be intricately carved as such. Soapstone is used in the Pudhu Mandapam as well, as seen below, above the pillars, and possibly the pillars themselves:

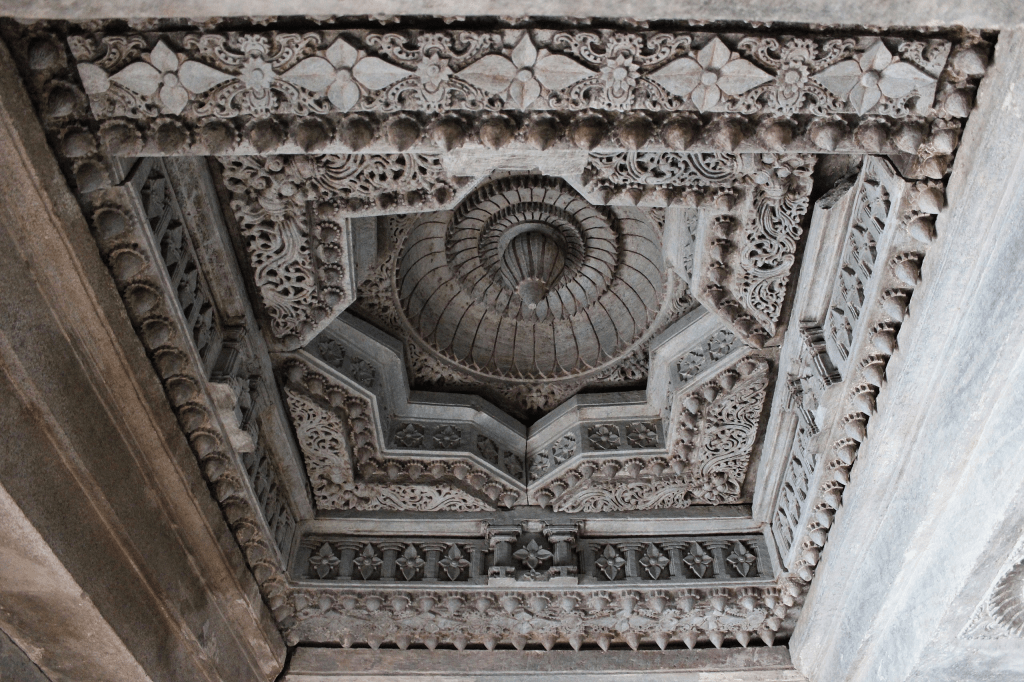

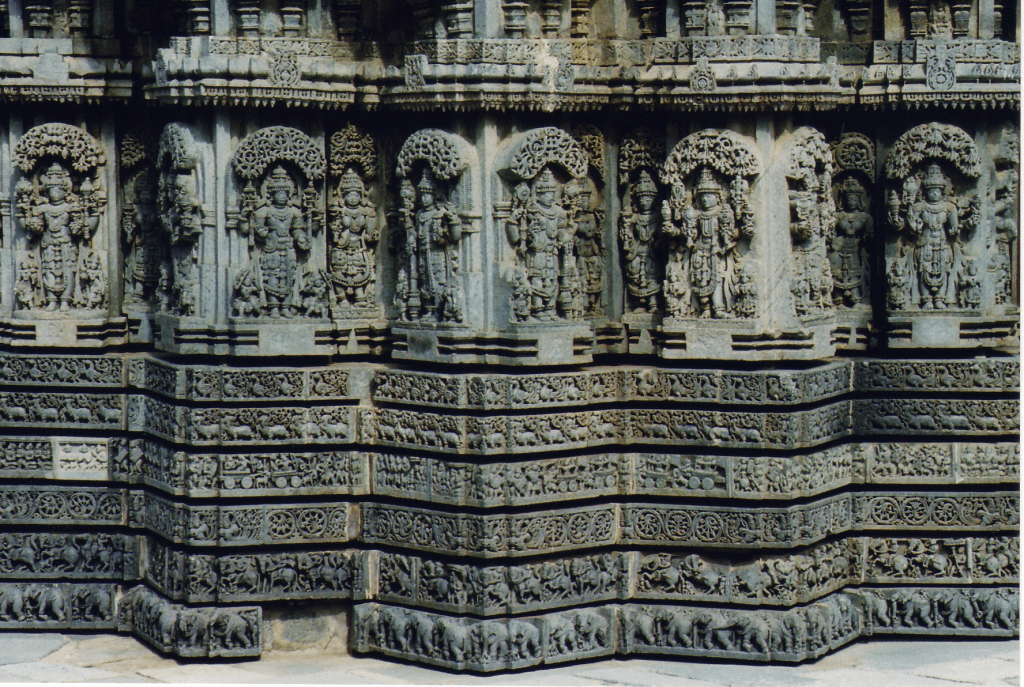

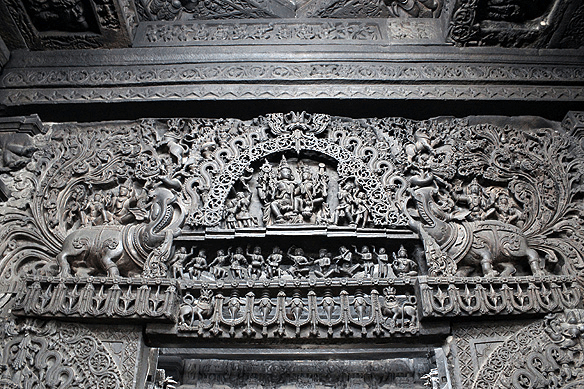

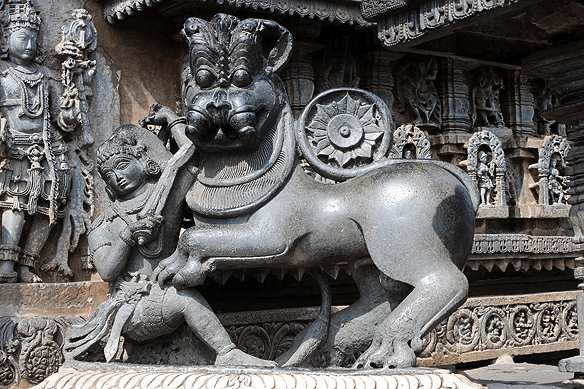

As shown, it’s in smaller sections of the Madurai Meenakshi temple, used for intricate carvings. We should aim to spread this use further, whether within the Madurai Meenakshi temple, Koodal Azhagar, or other temples, or palace and monumental building construction, in inner ornamentation rather than exterior, protected from the natural elements. As mentioned, it has been extensively used in Karnataka Hoysala temples, such as the examples below:

Above is a ceiling freeze of soapstone from Akkana Basadi in the Hassan District of Karnataka. Note the level of detail that’s able to be carved in this material, as well as in the soapstone Chennakesava and Hoysaleshwara Temples, also in the Hassan district below:

The exterior of the temple is shown, and the interior entrance to the sanctum is shown below:

The level of detail that’s able to be carved in soapstone far exceeds granite, as it is a soft material. It’s able to be finely polished to shine, as shown below, as well. With these benefits, it’s less suited to handle monsoon weather, high heat, and high humidity, all of which are present in the Tamil regions.

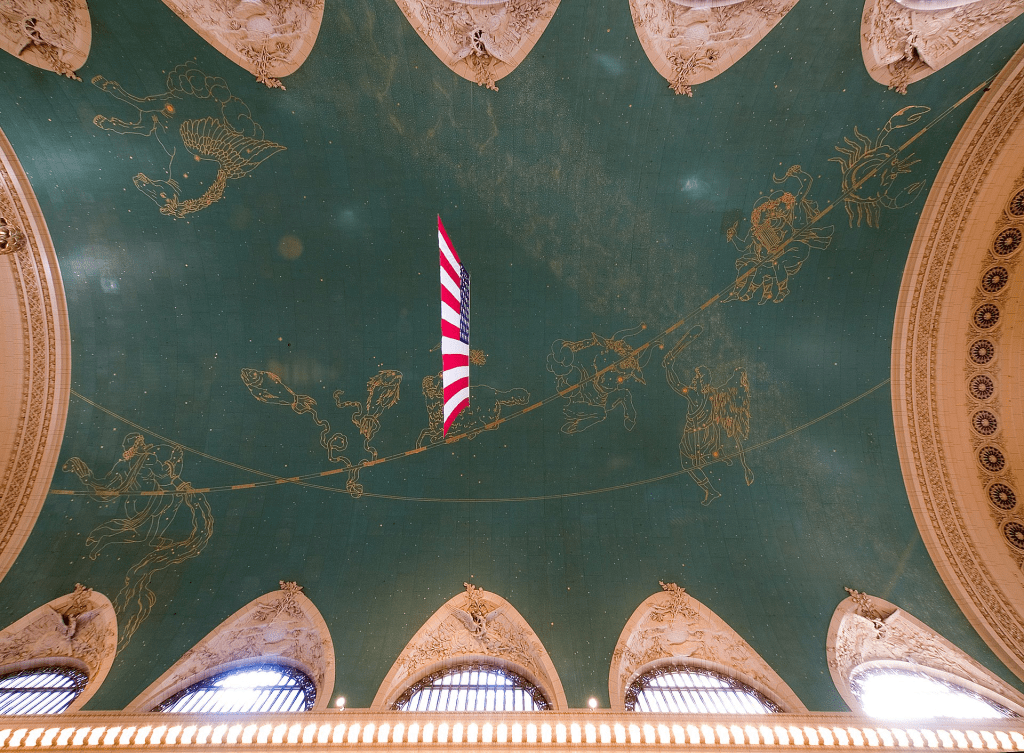

I propose we make a museum/cultural arts center in Madurai, with grand theater, Kacheri (concert), and cultural art displays. This museum should be of a grand scale, as is the metropolitan museum of art, or the grand central terminal –

while instead made of polished granite stone blocks and as the exterior construction, to make a lasting, monumental sculpture as the Portuguese had done, while using South Indian elements from Tamizh temples and palaces:

This museum could use granite inside, as well as soapstone and timber:

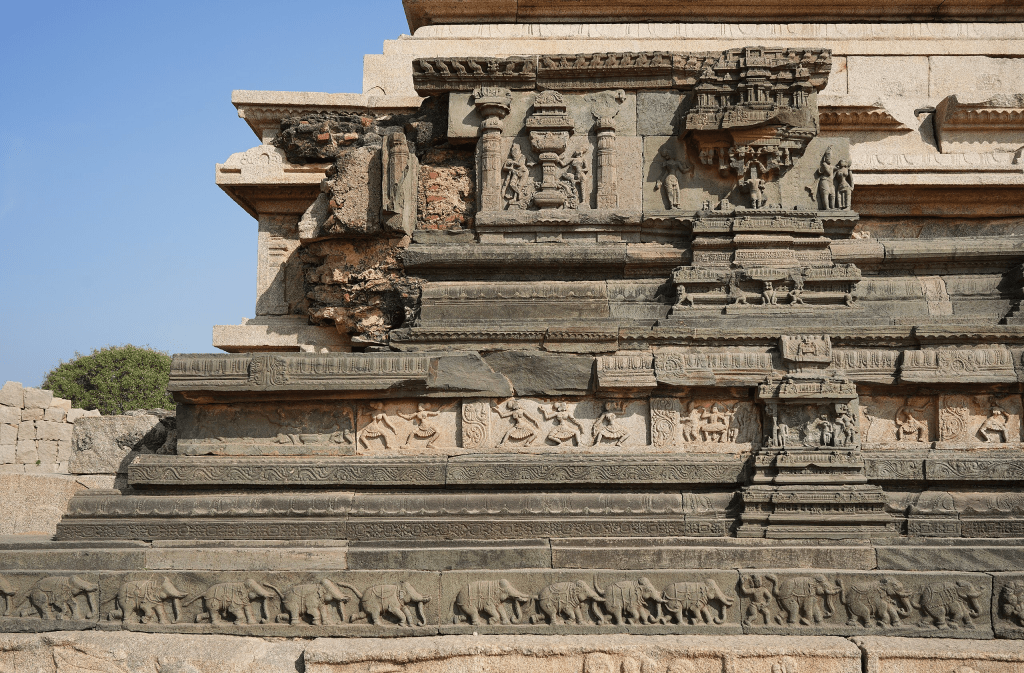

for intricately carved interior elements in limited areas, outside of the majority being granite carvings, such as these granite friezes on the Vitthala Temple in Hampi, which is similar to Tamil temples, though with a different color of granite – more light brown-pink in tone, while Tamil temples have a dark brown, black appearance. See the examples below of the Vitthala Temple in Hampi, Karnataka:

In general, Hampi has many innovative granite structures for citywide development that still survive, that we could model off of and evolve with, in Madurai. See the Mahanavami Dibba (throne platform) in Hampi, which has granite as a base platform with a layered green-brown stone in front, possibly of Chloritic Schist or Green Granite:

We could model off of many such structures as inspiration for our vision of Madurai.

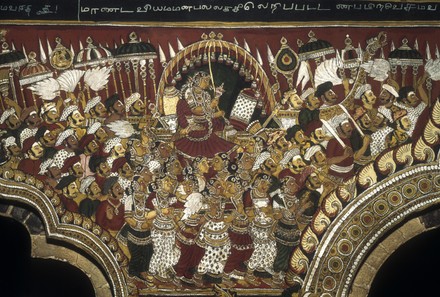

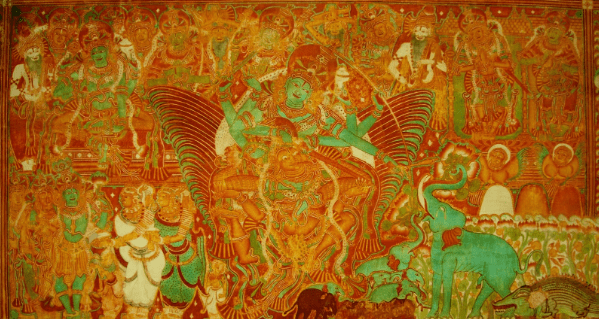

It could use friezes, multicolored, on the ceiling, in the style of Kerala Murals:

while taking inspiration from the ceiling of Grand Central Terminal, adding gold leaf to the murals where necessary:

Furthermore, we must enhance access to the natural wonders near Madurai, notably, Pasumalai and Kutladampatti Falls

Furthermore, Madurai is right next to the Western Ghats, around 3-4 hours of Munnar, Periyar National Park, Megamalai, and Kodaikanal, with lush greenery, mountains, and home to one of the largest biodiverse hotspots on Earth.

There was once a Madurai, before industrialization, with the Vaigai river running near the temple, the mountains setting the backdrop, and the temples and Thirumalai Nayak Palace standing tall behind.

The natural beauty of Madurai must be restored.

The writers of Sangam literature, the Pandyas, and Thirumalai Nayak saw a vision in Madurai, a city of art, dance, spirituality, and romance. May their dreams be realized.